Madelyn Cline’s Danica Richards in Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (2025)

Brook Rushton/Sony Pictures

[This story contains spoilers for the I Know What You Did Last Summer reboot.]

Jennifer Love Hewitt is addressing the years-old rumored beef between her and her I Know What You Did Last Summer co-star Sarah Michelle Gellar.

During a recent interview with Vulture, the actress, who reprised her role for the new I Know What You Did Last Summer movie, said that while she’s “not talked” to Gellar since the 1997 film’s premiere, there’s no drama between them.

“I honestly don’t even know what that was or how that all came to be,” Hewitt said of her alleged feud with the Buffy the Vampire Slayer star. “I just think people don’t want the narrative to be easy. Why do we always have to be against each other and out for each other?”

She added, “I haven’t seen Sarah. Literally, we’ve not talked since I saw her at 18 years old when the first movie came out. That’s why it’s so funny to me. People were like, ‘Say something back.’ And I’m like, ‘What am I going to say? I’ve not seen her.’ On my side, we’re good. I have no idea where this is coming from.”

Though Hewitt hoped to reunite with her at the new film’s premiere last week, Gellar confirmed on Instagram that they didn’t get a chance to see each other.

“For everyone asking – I never got to see @jenniferlovehewitt who is fantastic in the movie,” she wrote in one of her recent posts’ comments after fans noticed they didn’t pose together on the red carpet. “I was inside with my kids when the big carpet happened. And unfortunately JLH didn’t come to the after party. If you have ever been to one of these it’s crazy. I sadly didn’t get pics with most of the cast. But that doesn’t change how amazing I think they all are. Unfortunately some things happen only in real life and not online.”

The I Know What You Did Last Summer reboot, which hit theaters on Friday, follows a new generation of friends who are terrorized by a stalker who knows about a gruesome incident from their past. In addition to Hewitt, Freddie Prinze Jr. also reprised his role from the original pic. As for Gellar, while her character died in the 1997 movie, she makes a surprise appearance in the reboot during a dream sequence. Franchise newcomers include Madelyn Cline, Chase Sui Wonders, Jonah Hauer-King, Tyriq Withers, Sarah Pidgeon and Gabbriette Bechtel.

best sitcoms of all time, but it’s certainly one of the most popular. The show’s character-driven, pseudo-nerdy quirkiness has left a mark on the genre, and projects like the upcoming “The Big Bang Theory” spin-off focusing on Stuart Bloom (Kevin Sussman) are ready to expand the parent show’s universe in new directions. With so many “The Big Bang Theory” characters who deserve their own spin-off series waiting in the wings, who knows how long the franchise will endure?

“The Big Bang Theory” has been such a pop culture juggernaut that it’s even expanded its tendrils into the real world. The events of the show mostly take place in Pasadena, California, and in 2016, that city honored the CBS comedy by naming a street after the show. This, of course, is an absolutely useless honor in practice, and has almost certainly led to some people losing their cool with “TBBT” fans who excitedly emulate Sheldon Cooper’s (Jim Parsons) “three knocks and a scream” knocking on the doors of businesses situated near the street signs. Still, it’s a fun little nod to the sitcom’s popularity, and shows how the city of Pasadena has embraced its science-minded sitcom heroes.

Unfortunately, Pasadena didn’t go as far as renaming North Los Robles Avenue, where the show’s central apartment building is located. Instead, it opted for a far smaller street that’s actually much closer to an alley — but still, “The Big Bang Theory Way” does have a nice, if somewhat uncanny ring to it.

Should you wish to visit The Big Bang Theory Way, it’s a walking alley that starts from the southeast corner of Pasadena Memorial Park, just across the street from the Memorial Park metro station entrance. The alley runs three blocks from Holly Street to East Green Street, intersecting with Union Street and East Colorado Boulevard and meeting Exchange Alley on the way.

Don’t expect the alley to be plastered with “The Big Bang Theory” memorabilia or murals of Sheldon and the gang, though. The Big Bang Theory Way is a nice, but comparatively unassuming walkway sprinkled with picnic tables, bars, and cafés — but also plenty of fences, parking lots, and imposing doorless brick walls. Still, despite its plain appearance, don’t be surprised if you choose to visit and end up meeting like-minded tourists … quite possibly ones wearing Green Lantern shirts.

“The Big Bang Theory” is available for purchase on physical media and it’s currently streaming on HBO Max.

Charle Barnett’s Peter Mills was written out of “Chicago Fire” to make room for other characters. Barbie Ferreira left “Euphoria” because her character Kat Hernandez had limited storyline options left.

Sometimes, the departure of a star whom fans saw as key to a show’s popularity might be a simple contract issue. For instance, Regé-Jean Page’s Simon Basset left “Bridgerton” simply because his contract was up and the esteemed Duke of Hastings opted to go explore other things. A similar thing happened with Gina Torres, who starred in the USA Network legal drama “Suits” as Jessica Pearson for six seasons before departing the show in 2016. In an interview with The New York Times, Torres confirmed that her exit was the simple matter of her contract ending:

“My contract was up, so this wasn’t a power play that went terribly wrong.”

Torres also alluded to personal difficulties that made the decision to leave the show necessary:

“I think the public doesn’t understand the rigors of shooting a show for an actor, much less when you’re on location and away from home. At one point I approached [‘Suits’ showrunner Aaron Korsh] and said: ‘It’s not that I don’t love the show and love Jessica, who is my alter ego. But my life is my life, and I need to take care of it.’ And everyone was completely supportive. Leaving was hard, especially when I do so with a heavy heart. “

Torres, unfortunately, wasn’t kidding about the strain in her personal life when she gave that The New York Times interview in September 2016. In October 2016, she and her husband — “The Matrix” and “John Wick” franchise star Laurence Fishburne — quietly separated after being married for 14 years, and eventually divorced in 2018.

On the work front, Torres has been more fortunate. She has remained a highly sought-after actress after leaving “Suits,” working on a great many movie and TV projects and even revisiting her iconic “Suits” character in the short-lived 2019 spin-off “Pearson.” Interestingly enough, Torres even became part of another actor departure story — only from a radically different angle. In 2020, Liv Tyler’s Michelle Blake left “9-1-1: Lone Star” when the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible for Tyler to commute between her London home and the filming location. Her replacement on the show? Paramedic captain Tommy Vega, played by none other than Torres.

[This story contains major spoilers for 2025’s I Know What You Did Last Summer.]

It’s been an especially busy summer for Madelyn Cline.

She’s not only in the middle of filming the final season of her hit Netflix series, Outer Banks, but she’s also been simultaneously promoting this weekend’s theatrical debut of Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (2025). And that’s not even half of it. Just one month ago, she happily carved out time from her existing shooting schedule and flew from South Carolina to Los Angeles in order to film a new ending for her character in Robinson’s slasher.

In Jim Gillespie’s 1997 franchise launcher, I Know What You Did Last Summer, Jennifer Love Hewitt’s Julie James and Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Helen Shivers played best friends until the latter met her end in a heartbreaking duel with Ben Willis’ murderous Fisherman. In Robinson’s legacy sequel to that film and 1998’s I Still Know What You Did Last Summer, Chase Sui Wonders’ Ava Brucks and Cline’s Danica Richards are essentially the new Julie and Helen of Southport, North Carolina. (Spoilers ahead.)

Cline’s character is a former Croaker Beauty Pageant Queen à la Helen, and her (first) fiancé, Teddy Spencer (Tyriq Withers), is a wealthy loose canon just like Helen’s boyfriend Barry (Ryan Phillippe) was. However, thanks to test screening audience feedback, Danica no longer suffers the same fate as Helen, and Cline didn’t learn that her character would survive the newest Fisherman’s wrath until the middle of June.

“I only got the news that I was coming back about two-and-a-half weeks ago. We shot all those very, very end scenes about two weeks ago,” Cline tells The Hollywood Reporter during a June 28 press day.

June’s Los Angeles-based additional photography also included a new scene where Danica visits Helen’s grave and picks up a framed picture of her that’s been left behind. The purpose of this scene was to further set up the surprise return of Gellar’s Helen in Danica’s forthcoming dream. According to Cline, the nightmarish sequence itself was not a part of the original script, but it was eventually added during the rehearsal phase of production. Gellar twice posted from the Australia set as if she was only visiting husband Freddie Prinze Jr. for Thanksgiving last year. (Prinze Jr.’s Ray Bronson joined Hewitt’s Julie as two of the new film’s four surviving legacy characters.)

“I did not know that [dream sequence with Sarah Michelle Gellar] was happening. Jenn [Kaytin Robinson] texted me that we were going to do it. And I was absolutely floored. Gobsmacked,” Cline recalls. “She then sent me the sides and was like, ‘What do you think?’ And I said, ‘I absolutely love them, but whatever. The fact that we’re doing this, write whatever you want. I’m in. I will do whatever you want.’”

As for working with Gellar, Cline remains impressed with how casually she carried herself that day as both an actor and a mother.

“I do believe it was one of the most iconic days of my life, and I just felt like everything conspired for us to have that in the script. It only felt right for Danica to meet and face Helen,” Cline says. “It’s just so special to have that stamp of approval and to be ushered in as a next generation by Sarah Michelle. [She] is, and has always been, a force.”

Below, during a recent spoiler chat with THR, Cline also discusses her character being a source of comic relief and how her Glass Onion director Rian Johnson bolstered that side of her. Then she addresses her name’s inclusion in a couple years’ worth of Spider-Man 4 casting rumors.

***

To recap, you were raised in South Carolina, and that’s where you shoot your show about North Carolina [Outer Banks]. And now you’re starring in a North Carolina-set horror franchise. In the case of I Know What You Did Last Summer, is it a total coincidence?

Yes, it’s a very big coincidence, but I Know What You Did Last Summer was a North Carolina movie shot in Australia. So we’re branching out. We’re getting further and further away.

Outer Banks, Glass Onion and I Know What You Did Last Summer all have summer vibes. Your next two movies also have summer vibes, and there’s a couple past indies of yours that have summer vibes. Does this town think you’re allergic to winter climate?

Yeah, I think so. I do believe there’s something about my vibe that doesn’t give winter. I don’t know if it’s the fake tan or the frosted tips, but the running joke that I can’t get away from boats is so funny.

But you will do snow if it comes your way?

I would love to do snow, but I just don’t trust snow’s continuity.

Growing up, when you weren’t watching reruns of Seinfeld and Friends, did the Last Summer movies make their way onto your radar at all?

No …

The I Know What You Did Last Summer movies never reached you?

Oh, sorry, I thought you said Last Summer movies.

My fault. I was doing that Hollywood thing where nobody says the full title of anything.

(Laughs.) Yes, let’s abbreviate. But I wasn’t allowed to watch horror at all. So the first time I saw the original was probably during a sleepover at a friend’s house whose parents did allow horror movies to be watched. And I probably watched it [through my hands] because I was a big fraidy-cat. But then as I got older, my taste changed, and I began to love horror-thrillers and psychological thrillers.

The original movie is one of my best friend’s favorite movies, and when this audition came around, we rewatched it. And it’s so funny because Outer Banks shares some of the production crew that shot the Last Summer movies. (Cline cracks herself up upon calling back to my franchise abbreviation.) So it’s always been around and a part of the aura.

Madelyn Cline’s Danica Richards in Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (2025)

Brook Rushton/Sony Pictures

Danica is a very comedic character. She’s quirky and, dare I say it, loopy. I know he’s praised your comedic instincts in the past, but was Rian Johnson the one who gave you the confidence that you could do comedy?

Yes, absolutely. A hundred percent. I remember being on set for Glass Onion and watching Kathryn Hahn, Kate Hudson and Daniel Craig just lean in and be so free. My first job was also with Danny McBride [on Vice Prinicipals], and I had the same kind of realization there. But to hear that from Rian and to get that stamp of approval, that’s when I realized, “Oh, I think I want to do this.”

I spoke to you ages ago for a very peculiar horror movie called The Giant, and you said something that’s been stuck in my head ever since. You said the most frequent note you received from the director was the phrase “low and slow.” (It makes sense to anyone who’s seen the movie.) Were Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s notes on the complete opposite end of the spectrum?

Yes! Since then, it’s actually been the opposite most of the time.

High and fast?

Yes, high energy and fast pace.

When you first read the script, did you correctly guess the killer reveal?

No, I did not. When you’re reading any kind of whodunit for the first time, you’re immersing yourself in the story and you’re trying to guess, but you’re looking in all the wrong places. That’s exactly how you know a whodunit is written correctly.

So even though you worked with Mr. Whodunit, Rian Johnson, your guessing skills are still …

Terrible! I have the survival instincts of a pickle.

Tariq Withers, Sarah Pidgeon, Chase Sui Wonders & Madelyn Cline in I Know What You Did Last Summer

Brook Rushton/Sony Pictures

After the accident, Danica drives into a parking garage, and I loved this ice-cold look you give in the rear-view mirror. When you go for late night drives with four of your closest friends, what percentage of the time are you the one driving?

I used to [drive] a hundred percent [of the time], but as I get older, I realize the liability. So it’s probably more like 60-40 now.

When you and your co-star Jonah Hauer-King first encountered each other on set, who was the first person to reference Rocky III?

(Laughs.) I don’t know, but Jonah was in Harry Potter.

Oh, was he?

Yeah!

In case my reference was too vauge, you and Jonah previously made a movie [This is the Night] that’s partially about Rocky III.

Oh fuck! He keeps mentioning that, and I keep forgetting. We had a shoot last week, and he was like, “Madelyn and I shot together before.” (Cline mimics Hauer-King’s British accent.) And I was like, “What are you talking about?” But we’ve had this conversation so many times. I don’t know why I blocked it out of my head. (Laughs.) Maybe it’s because we [filmed] in Staten Island.

[The next eight questions/answers involve major spoilers for 2025’s I Know What You Did Last Summer.]

This is the part of the interview where we transition into spoiler questions. Firstly, the dream sequence with Sarah Michelle Gellar’s Helen Shivers. How did that go down?

That was not in the original script. I did not know that was happening. I was on the way home from a rehearsal, and Jenn [Kaytin Robinson] texted me that we were going to do it. And I was absolutely floored. Gobsmacked. I could not believe what was happening. She then sent me the sides and was like, “What do you think?” And I said, “I absolutely love them, but whatever. I don’t care. The fact that we’re doing this, write whatever you want. I’m in. I will do whatever you want.”

I do believe it was one of the most iconic days of my life, and I just felt like everything conspired for us to have that in the script. It only felt right for Danica to meet and face Helen, and look in the mirror and see herself. Also, almost every character in this movie gets to have the baton passed to them from an original cast member. It’s just so iconic and so special to have that stamp of approval and to be ushered in as a next generation by Sarah Michelle.

Could you tell if Helen’s return was surreal for Sarah?

No, she was just cracking humor all day. She was ordering lunch, and she was mom the whole day. We were having a great time. The whole family was there, and we shot it on a Saturday. So it kind of felt like an off day, but also an on day. It felt casual and really chill and very familial. But Sarah Michelle is, and has always been, a force.

Madelyn Cline’s Danica Richards in Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (2025)

Matt Kennedy/Sony Pictures

There’s a graveyard scene where Danica looks at Helen’s photo and relates to her as a fellow Croaker Pageant Queen. Was that also added later to set up the dream sequence?

Yeah, it was added when we did additional photography in L.A. months after our shoot [in Australia].

Most importantly, was your character saved in post-production? Did test audiences revolt over Danica’s death, leading to additional photography?

From what I’ve heard, allegedly, yes.

I was also really frustrated by your character’s death, so I’m glad that was undone.

Thank you. I only got the news that I was coming back about two-and-a-half weeks ago.

What!? Two weeks ago? [Note: This interview was conducted on June 28.]

Yeah, we shot all those very, very end scenes about two weeks ago.

Oh my God, movie magic.

I know, I know. How crazy.

You mentioned that I Know What You Did Last Summer, aka Last Summer, is one of your best friend’s favorite movies. Have you shared these secrets with her?

I haven’t told her. She’s coming to the premiere, and I want to hear her scream.

[The spoiler section for I Know What You Did Last Summer has now concluded.]

Sony is behind I Know What You Did Last Summer. They’re also the proprietors of those Spider-Man movies. Maybe you’ve seen them.

I have!

Your name has been thrown around in various Spider-Man 4 rumors the last couple years. Is there any truth to them? Or did someone take your Spider-Gwen Halloween costume too seriously?

Never say never. Look, I am a huge fan of Spider-Gwen, but I haven’t heard anything.

I always assumed your Spider-Gwen costume was a reference to your True Grit audition.

(Laughs.) I know! I feel like Hailee [Steinfeld] and I have had these parallel lives and loves. But no, I’ve always just loved Spider-Gwen, and that costume was made by a local artist [in South Carolina]. It was the best one I’ve ever seen, so, of course, I had to wear it for Halloween.

You’re filming the final season of Outer Banks right now. Does this feel like the right time to wrap, at least for you?

I think so. We’ve told the story we need to tell, and everybody, of course, loves it. But at the same time, just like our characters, it’s time for us to grow up again in a way. It’s the same thing for the original cast of Last Summer. It’s time for us to pass the baton and usher in whoever the next generation is in the Outer Banks universe.

The Notebook was set and filmed in South Carolina, and if you were to remake that, no one could dispute that you’re now the queen of Carolina fiction.

It’s beautiful down here. The locations are beautiful, but very buggy. On our call sheet yesterday, it, in very, very official language, said: “Mosquito-y location. Dress accordingly.” That’s like every location down here, though. But I’m a huge fan of The Notebook, and I’m a huge fan of shooting here. My family is still down here, and I have a great, great love for it. So maybe we will.

Madelyn Cline’s Danica Richards in Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (2025)

Brook Rushton/Sony Pictures

Decades from now, when you’re reminiscing about the Last Summer experience, what day will you likely recall first?

I’ll always recall the first day when I was so incredibly jet lagged. I got off the plane, and Chase [Sui Wonders] and I immediately walked to the Sydney Opera House. And I remember thinking, “Am I still drunk from the plane? Or am I jet lagged? I don’t know which one.” (Laughs.) We then texted Jenn a picture of us outside the opera house, and we were like, “We’re here!” And then everything else was just off to the races.

I promise I won’t put, “Am I still drunk from the plane?” in the headline of this piece.

You can put it in the text below it.

The DEK, as we call it.

(Laughs.) Yeah, the DEK!

***

I Know What You Did Last Summer (2025) is now playing in movie theaters.

“Star Trek” and “The Twilight Zone” invite comparison. They’re both early science-fiction television that are still classics today. They didn’t actually air at the same time (“The Twilight Zone” ran five seasons between 1959-1964, while “Star Trek” aired three seasons between 1966 to 1969) but retrospectively, they feel like products of the same TV era. Both programs also reflected the social consciences of their creators, Rod Serling and Gene Roddenberry respectively, by using sci-fi stories mostly as allegory.

But while “Star Trek” can be occasionally scary, “The Twilight Zone” was often a full-on horror show. One of the scariest episodes is “It’s A Good Life.” (The episode, scripted by Serling himself, was based on a short story of the same name by Jerome Bixby.) The episode’s monster is Anthony Fremont (Bill Mumy), a little boy but not an ordinary one. Anthony is a god in corporeal form, one who has all the maturity and wisdom you’d expect a six-year-old to have. He’s walled his hometown Peaksville off from the rest of the world, controlling the townspeople’s lives, entertainment, food supply, etc. They don’t even have freedom in their own heads because Anthony can read minds. If anyone so much as thinks a bad thought, then Anthony sends them to the Cornfield. What is that? It’s probably for the best we don’t know.

“It’s A Good Life” holds up as one of the most famous “Twilight Zone” episodes. It’s also one of the many “Twilight Zone” episodes that have been turned into “Treehouse of Horror” segments on “The Simpsons,” specifically “The Bart Zone” in “Treehouse of Horror II.” (Bart, naturally, is Anthony.)

The 2002 “Twilight Zone” revival also included a sequel to “It’s A Good Life,” titled “It’s A Still Good Life.” Written by Ira Steven Behr (a name Trekkies might recognize from his work writing on “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine”), the episode followed a grown-up Anthony. Mumy, who was now almost 50 and still a working actor, reprised his role, as did Cloris Leachman as Anthony’s mother. (Anthony’s father, played by the then-retired John Larch, had since been sent to the Cornfield.)

Because Anthony was never challenged, he never had to grow up. He’s still as self-centered and vindictive as a little child often is. Worse, he also has a daughter named Audrey (Mumy’s real daughter Liliana), who has inherited his powers.

“It’s A Good Life” is such a famous “Twilight Zone” episode that “Strange New Worlds” can say the word “cornfield” and still trust its viewers will pick up its meaning. Unlike Anthony, Trelane at least has parents who are able to put him in his place.

“Star Trek: Strange New Worlds” streams on Paramount+, and new season 3 episodes premiere on Thursdays.

Gene Hackman as a leading man until they saw him whoop it up as Buck Barrow in “Bonnie and Clyde,” nor was Renée Zellweger a cinch for stardom prior to her incandescent performance in “Jerry Maguire” (for which she wasn’t even nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar, but that’s another outrage for another time).

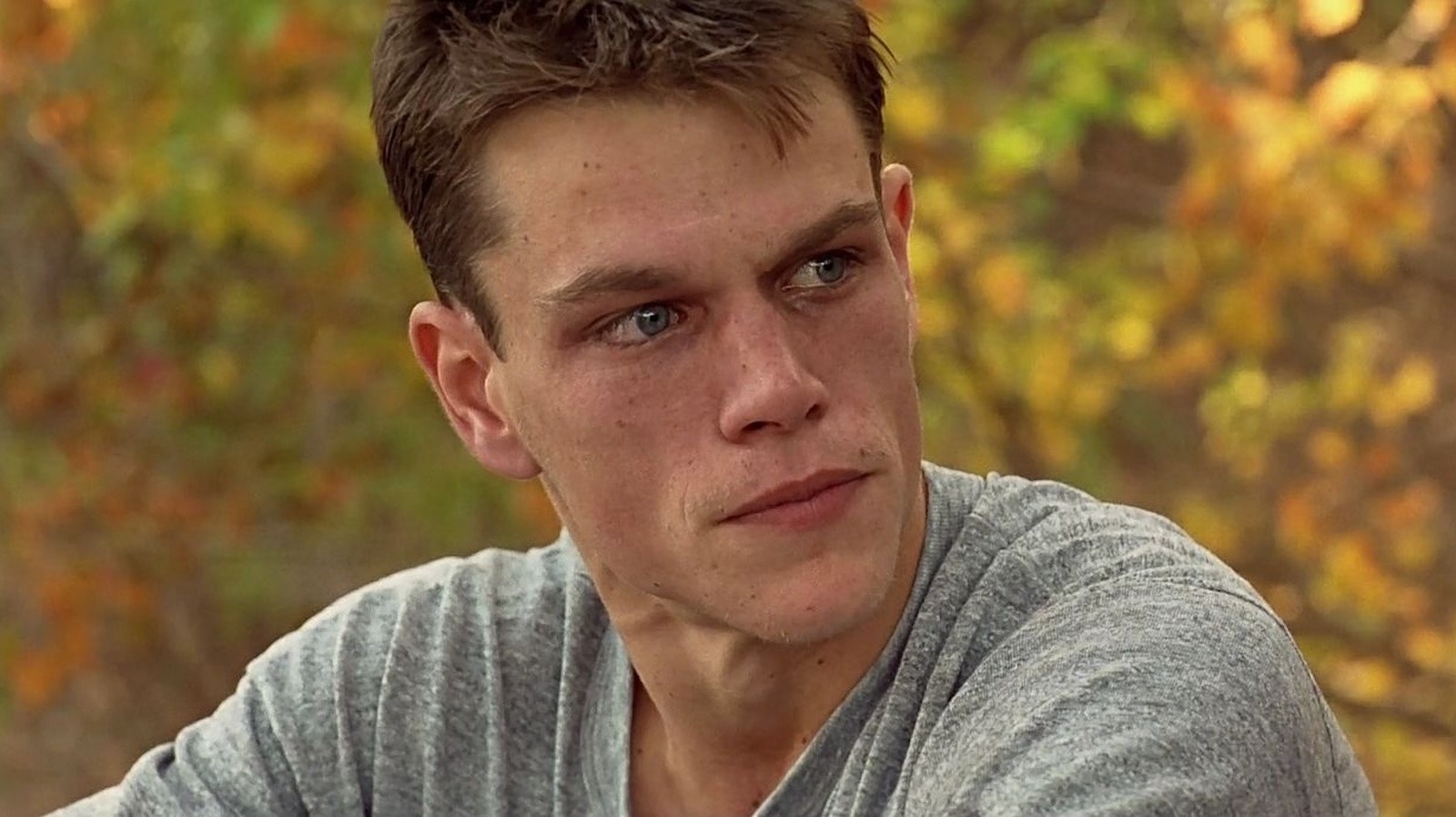

Matt Damon was another show-me star.

It’s to his credit that I remembered him from his small part in “Mystic Pizza” when I saw him play the antisemitic antagonist of “School Ties,” and he was impressive in Walter Hill’s “Geronimo: An American Legend” if only because he held his own with the powerhouse likes of Hackman, Wes Studi, Robert Duvall, and Jason Patric. He still had a babyface, but he exuded confidence. Like any aspiring actor, he knew he belonged. He just had to prove his worthiness to the folks who did the casting. To do so, Damon took on a role in a great Denzel Washington war movie that nearly killed him.

Director Edward Zwick knew from launching movie stars. He caught Denzel Washington at the right time when he cast him as the slave-turned-soldier Trip in “Glory,” and made Brad Pitt’s stardom official with the unabashedly melodramatic Western epic “Legends of the Fall.” Two years after scoring a box office hit with the latter, he took on the prestige Gulf War drama “Courage Under Fire,” which came attached with two of the biggest stars in Hollywood at the time, Washington and Meg Ryan. Written by Vietnam War veteran Patrick Sheane Duncan, the film was a “Rashomon”-esque account of a Gulf War firefight in which Ryan’s Medevac captain is believed to have died honorably. Washington’s character is tasked with determining if her actions were worthy of her becoming the first woman recipient of the Medal of Honor.

Washington receives conflicting accounts from members of Ryan’s crew, but finally uncovers the truth when he interviews Damon’s haunted Andrew Ilario. Ilario has worn himself down to a nub via heroin addiction, but is able to accurately recount what went down during the operation. It’s an incredibly powerful scene, primarily because Damon looks like a human skeleton.

In a 2016 Reddit AMA, Damon wrote the following about his preparation for the scene:

“I weighed 139 pounds in that movie, and that is not a natural weight for me and not a happy weight for me even when I was 25. I had to run about 13 miles a day which wasn’t even the hard part. The hard part was the diet, all I ate was chicken breast. It’s not like I had a chef or anything, I just made it up and did what I thought I had to do. I just made it up and that was incredibly challenging.”

Damon once told Charlie Rose that he nearly killed himself to nail this scene, which he considered a “business decision.” As he said to Vanity Fair in 1997, “I thought, ‘Nobody will take this role, because it’s too small.’ I was sick of reading scripts that [his ‘School Ties’ co-star] Chris O’Donnell had passed on, and I was looking for something to set me apart: ‘Look what I’ll do, I’ll kill myself!’ Directors took note of it.”

Damon had to wait a year for this performance to bear fruit, but he had to be thrilled when the director who took note of his physical sacrifice was Francis Ford Coppola. While Damon is terrific in Coppola’s “The Rainmaker,” he’d already made his own luck by co-writing (with Ben Affleck) and starring in “Good Will Hunting.” From that point forward, Chris O’Donnell was getting the scripts he passed on. And you’ll see him next on the big screen as Odysseus in Christopher Nolan’s “The Odyssey.”